Without plants, we wouldn’t have air to breathe, and we also wouldn’t have these great stories inspired by the leafy green vegetation. This week’s episode, produced in partnership with The Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, features two stories from scientists of the cutting-edge research institute at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who had plants impact their life and science.

Part 1: While everyone around Anthony is impressed with his plant PhD research, he isn’t sure if he actually knows what he’s doing.

Anthony got his Ph.D. in Belgium where he studied the impact of the environment (such as high temperature and dry spells) on the vegetation in a grassland. He now works as a postdoc at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign.

Part 2: Scientist Jessica Brinkworth turns to gardening in the midst of a burnout.

Jessica Brinkworth is an assistant professor and evolutionary immunologist in the Department of Anthropology. She directs the Evolutionary Immunology and Genomics laboratory at UIUC. Her research program revolves around a basic question “why do we get sick?” Her work demonstrates profound differences between humans and closely related primates often used as medical models in power and specificity of immune responses to severe infections, and as well as how chronic social stress alters immune function. Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 her lab has worked with Illinois agricultural workers, focusing on the effects of labour environment on immune function and disease susceptibility. Prior to and during part of her academic career, Brinkworth was a policy analyst in health risk management and later biologic drug regulations for Health Canada.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

When I was doing my PhD in Belgium, I got to spend a lot of time in a grassland. This is because I was walking on the team with different partners and we're interested in the impact of the climate on this grass and vegetation.

And because I was the plant physiologist in the team, I was the one going there and dealing with the plants. Twice a week, I was going there to monitor the vegetation and take measurements.

My typical field day starts at 8:00. As soon as I arrive there, I need to hit the ground running because I have to take 100 measurements every two hours. So the I have to go there, get rid of the cows that are grazing there because dozens of cows are in my plots.

Then I need to select 100 plants and get them ready for the measurements by putting them in the dark with a little grass pin. And then I have to go over all of those 100 plants and measure them with the instrument in order to get something that's called chlorophyll fluorescence, which is a weak light that's emitted by plants. And that can give you information about how healthy the plant is.

Then once I'm done with measuring those 100 plants, I need to repeat this process again because that's something that I have to do every two hours. I just spend my day circling around this field, in this section of isolating plants, measuring them, studying plants, measuring them. And this is something that I do at 11:00, 1:00, 3:00 and 5:00, which makes a lot of squats in a day because those are grass. They're on the ground. So each time, I have to get on my knees to put those grass pin on them. Which made me like rainy days because I didn't have to go in the field in those occasions.

So when I'm not in the grassland, when I'm not in the field taking measurements, I'm in the lab either organizing my data or coding on my computer or trying to learn as much as I can about chlorophyll florescence. Because it turns out that it's not an easy thing to analyze. There's still a lot of debates in the scientific community about the meaning of some tiny variations in this emission of light.

And because this was the first time we were doing this kind of measurement on campus and at the lab, this was something that I had to learn by myself. This was an expertise that I had to develop by myself.

I remember days where I was just spending hours trying to understand the difference between two different variables just to find out later that this was actually the exact same thing but under a different name and some time calculated a little bit differently, which makes you feel quite dumb, honestly.

But despite of that, when people wanted to learn about fluorescence, were interested to know if this was something they could use in their own research, they would come to me and ask for advice and what I could teach them about that.

So on those occasions, I would quickly put up a quick introduction on the subject and then we would look at data together. See how to analyze them and what you can learn from them.

Then, often, we would go where the next plantation was taking place and just look at the plants together, the setup and see what could be done, what was the best approach, the best way to measure those plants.

That was a really, really fun thing to do collaborating with the other PhD students. It was great also because I was feeling a bit helpful. It was nice to have other people interested in what I was doing. And collaborating is always a lot of fun.

And it was not only PhD students who are interested in what I was doing. I still remember by the end of my PhD, I was invited at a strategic meeting with all the faculty members because they were trying to put up a new project on campus that was using a new facility that was being built. I was the only PhD student at the table, which made me very proud because there were all those bright minds really interested in what I had to say. They were eager to learn about what I was doing and they were asking how that could be used in the new project that they were putting up.

To be recognized as an expert at something that they put so much work on, so much effort, that was kind of intoxicating somehow. I was probably a little bit full of myself by the end, I have to admit. But I was very proud of that.

And so fast forward dozens of meetings, thousands of lines of codes and hundreds of papers, 16,500 measurements in the field, here I am at the lab in front of my computer. It's the end of my PhD thesis and I'm staring at this document that’s what is going to be my first research paper, something I've been working months on.

This is everything I've ever longed for, my first publication. I've put in everything I've learned in this grassland. This is the very reason I've been doing the sheepdog with those cows in the field those past few years.

And I'm frozen because here in that lab with no cows around, the presentation to make, no plants to measure, I can start to hear my own thoughts for what feels like years. What those thoughts say really took me by surprise. Because what they were saying was what if I'm wrong? What if all this time I've been wrong? What if I just did not understand what I was reading in those papers? What if I've not analyzed it the proper way or what if I’ve misinterpreted everything?

And those thoughts were petrifying because this paper was about to be sent to an international journal. And before publication, it needs to be read by other scientists and experts at their fields that know certainly much more than me.

Then they would send those reviews to my PhD advisor and I and just expose how wrong I was all this time. And then my PhD advisor would turn back to me and say, “Hey, were you just making things up? I thought you got it. I thought that you know what you were doing? Maybe I was wrong to trust you with that.”

And what I could also see was just my entire world collapsing because every people I ever thought about, for instance, or collaborated with will learn from that and then I would be ostracized by the scientific community. And on that ____ [00:07:23] would just living a complete nightmare with my eyes wide open.

That's when I realized I was just so afraid to be wrong, actually. I was so afraid to be put into question and to put an end to that fantasy, this fantasy of me being an expert at something. That was petrifying, honestly.

That's when I realized that I actually needed to be challenged. I needed to be told when I was wrong even if it's hard to hear. I needed to learn from other people. If I were to not do that, if I don't put myself into this kind of situation, I would never grow. I would never learn anything and I would just maintain the decision about myself, a decision that's wrong.

And so when I realized that, I closed that document and started writing an email to my PhD advisor saying, “Here's the paper. I did the best I could based on the literature, but I think it would be good to have another set of eyes on it. What do you think?” And then I hit send.

I was still anxious but I know that that was the right thing to do. I know I would learn a lot and this made the anxiety easier to bear.

Thank you.

Part 2

The morning I started my position as an assistant professor, my eyes flew open at 3:30 AM and I was filled with anxiety about getting tenure and keeping my job. So I got up then got right to work on a grant and a paper.

And I kept this routine up for years, getting up at 3:30 in the morning and working. The reason I did this is because faculty jobs are rare. I had landed one and in an intensive research university to study comparative immunology and I was convinced the department had made a mistake, because they should have known that I didn't know what I was doing.

Worse, I had dragged my family here and we had arrived broke, so I could not lose this job.

But I really feared losing this job because I've been told directly by multiple senior faculty during my PhD that I would never land such a position. I wasn't a serious scientist. I was actually fundamentally unscholarly and the biggest waste of time, according to one of these senior faculty members who had made no secret about how undeserving he thought I was to be a PhD student and had very actively tried to chase me out of the program. So I had arrived at this job knowing I was an impostor.

On a July morning, three years into this early morning routine, I sat in my usual writing spot, which was a white armchair in my infant's empty, unfinished bedroom. I had my laptop on my lap, coffee in my hand, and I opened up a new site. I ended up reading news of just truly terrible political cruelty and chaos. At that moment, I felt completely and totally without agency.

What started as, “I can't do anything about this chaos,” fired off a cascade of just agencylessness. “That guy was right. I'm actually the biggest mistake my program ever made. I don't belong here. I can't do the work. I have no future in this career,” to, “I have let everyone down.”

And at that moment, after decades of working long hours, seven days a week trying to demonstrate that I was actually worthy of a research job, I finally burnt out.

I lay in this chair, my hands are like hanging over the side and I'm just staring at paint bumps on the ceiling. And I couldn't write because what was the point? I had no future in this job.

But then I was up, so I had to do something. I ended up flipping around Netflix looking for a show that was soothing and found a raft of gardening show episodes.

A few days went by and I was still bottomed out, but I was still getting up at 3:30 in the morning. And so each day, I made coffee and I opened up a gardening show. By this point, I had stopped writing science results altogether.

Gardening shows are really interesting because they're really pleasing content. A piece of land is planted with plants and seeds, shovels make these really pleasant noises cutting into the earth and things grow, so it's very soothing.

So that's what I did for the rest of the summer. Eventually, it was August and I really needed to get back to writing and writing up classes and the things that professors do. So, logically, I started watching a documentary about climate change and sustainable agriculture in Illinois, which doesn't have a whole lot of overlap with my job.

But I watched farmers and scientists touching soil and talk about rehabilitating the land and sinking carbon with crops and a switch was flipped in my head. I thought, “Ha, this is my next step!”

And I felt like this light of inspiration inside of me for the first time in months, or maybe years. So I danced down the stairs that morning for breakfast and I was yammering away about how I was going to drag my lab program in Immunology into Environmental Stewardship and Responsibility.

It was a great morning because, you see, lab science is really wasteful. Low‑end estimates are that science labs alone generate 5.5 billion tons of single‑use plastics annually. Since I was a graduate student, I've been really uncomfortable with the amount of waste that we were generating in the research I was doing.

But you see, serious scientists don't think about these things. Serious scientists make high impact findings and they get big grants. But I had big findings and grants. And as far as I could tell, I still wasn't considered a serious scientist.

And since I wasn't, that morning I thought, “Okay, well, I'm a PI now. Even if I'm not going to stay in science, I might as well try to do something about the waste that I generate.”

So when I got to the lab that morning, I was just beaming. I had a purpose.

I was supposed to be meeting with one of my undergrad interns Kyle Boshardy to discuss an ethics paper but, by the time he arrived, I was just bouncing with energy about gardens.

“I know what we're gonna do next,” I exclaimed.

He came into my office, “What?”

“We're gonna start a goddamn garden.”

“What?”

“Here on campus, we're going to try to offset a little bit of our lab plastic waste and emissions with a garden that sinks carbon,” and Kyle was all in.

He sat down we threw ideas back and forth, like, “A garden that will sink carbon. A garden in a disused forgotten space. Permission? We don't need permission. We are on a mission. We're gonna ask forgiveness. It'll be a renegade garden.”

And then the logical question came up. “Hey, do you know how to garden?”

“No. You?”

“No. And I have to admit I've actually killed a lot of house plants.”

So that night, I started to realize how very little I know about gardening, carbon sinks or even just climate change in general. I mean there are hundreds if not thousands of people in the US that specialize in this research and many of them have advanced degrees. And I had what? Like two hours with a documentary that quoted the Rodale Institute.

Then I could hear a little voice in my head, “You aren't a serious scientist. You'll lose your job. You'll let everyone down. You are an impostor.”

And for the first time in years of being bullied in science, I started to push back, albeit just against my little voice. But I really, really want to build this garden. I need this garden. Because I need something that will make me feel good and pull me out of this dark space.

So in the night, staring at the ceiling, I thought, “Fuck them. This is my foothold to a better space.”

I thought maybe I could get by with just some plant recommendations, so I reached out to a bunch of scientists that were doing research on carbon sequestration. And if you thought this was a really nice idea, but that the act of growing biomass that would eventually release gases with the intention of reducing gases wouldn't do much to offset anything, and that really brought me down. Like why hadn't I seen that before? If you grow stuff to sink carbon and that stuff rots, it's going to release gases when it breaks down.

So I mentioned the project to a senior faculty member in a research group I attended and she responded with one of the most harrowing things that a scientist can say. “Shouldn't you be focused on tenure?”

Yeah, probably, but I've decided to build a garden.

So Kyle and I spent a few weeks digging into greenhouse gas generation by households trying to figure out if the garden could be useful in reducing that kind of waste. It turns out that rotting food makes the greatest contribution to greenhouse gases in most households.

“Okay. So we'll compost in it.” The garden will be a beard for a trench composting system on campus.

A few weeks later, we had a chance meeting with a colleague in facility and services at the university and they patched us to the university powers that be that gave us permission. And they patched us to the Student Sustainability Committee who funded it. And so now our garden was no longer renegade, it was an administratively‑approved garden and it was going to do something that the campus hadn't been able to do, compost.

But we still didn't have any plants.

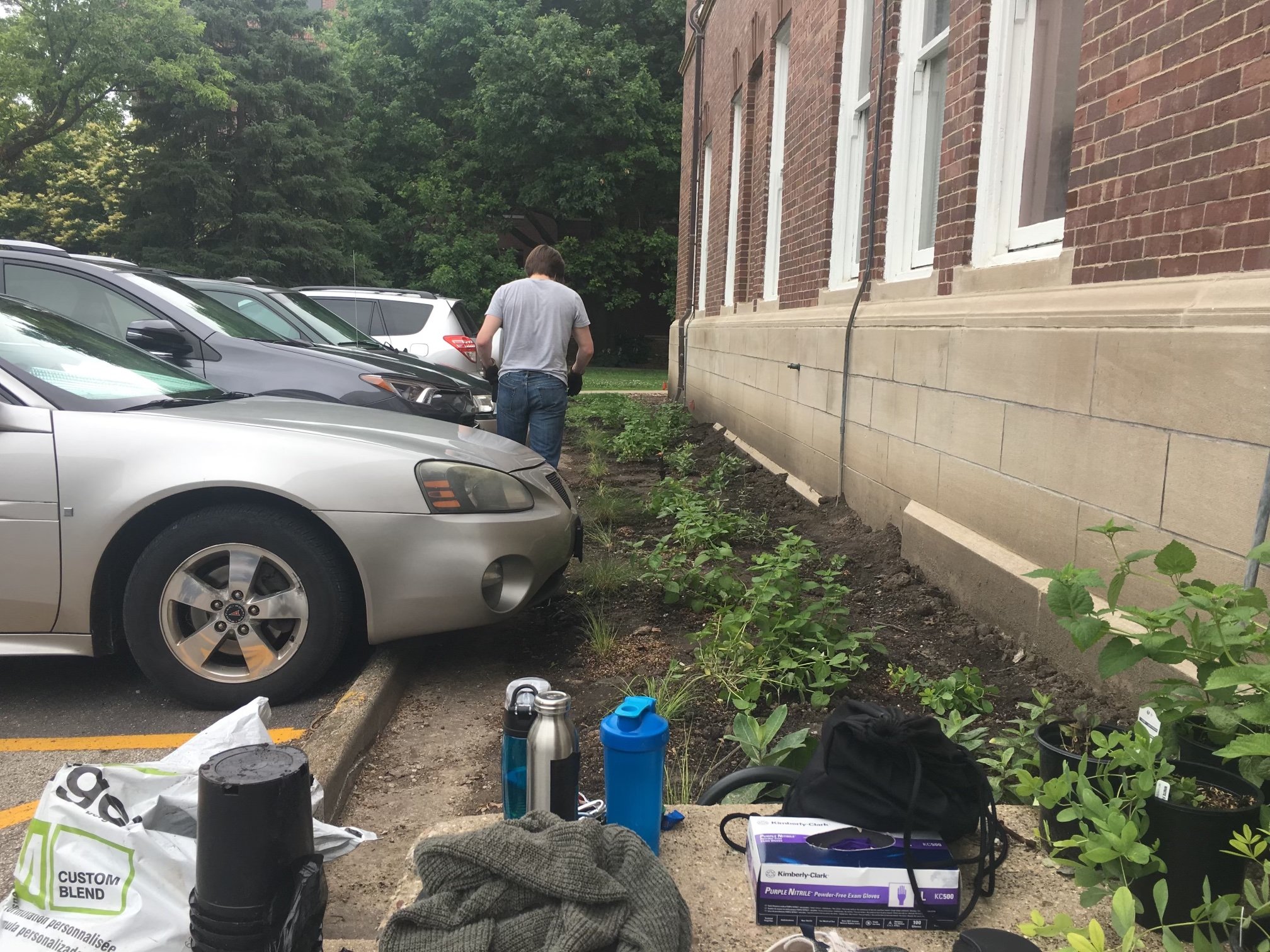

So a few days later, Kyle and I are standing at the prospective site. It's this 70‑foot strip of barren earth between the Anthro building and its parking lot and nothing is growing. No weeds. The ground's really hard. It's like crumbled asphalt and nitrogen‑depleted clay and it's infested with rusty nails and food trash and old roofing tiles. It looked completely impervious. Like what the hell could grow here?

So I squatted down and I was poking at the ground with my fingers. I thought, “Okay. Well, what would have grown here?”

Then it occurred to us, “Okay. What if we plant the plants that actually belong here? Like indigenous plants. Who would be here if we weren't deciding what plants should and shouldn't be on this land?”

The literature is filled with adaptations that clay‑loving plants have made, like sinking nitrogen and hosting fungi that can do that as well. So whoever can do that probably has the best shot in this space. They would probably also survive our really crappy gardening skills.

So we got to work. Laptops open, looking for plants that are native to central Illinois and could survive on the contaminated land around the Anthro building. That spring, dozens of plants arrived to my office and they were installed in the university greenhouses where the lab members checked on them daily. Pretty soon, little breaks to check on the plants became the best part of my work day.

By this point, I had long stopped getting up at 3:30 in the morning and it took very little to send me over to the greenhouse to push around little pots. I was just so happy to see these plants grow.

At a faculty meeting right after one of these visits, I was so happy that I excitedly told a room of stunned colleagues that the lab team and I were building a garden to sink carbon and support pollinators. And there is this big, almost endless pause.

“Okay. Thank you for that note, Jessica.”

And then I thought, “Goddamn it. The cat is now totally out of the bag. Now, they know I'm not a serious scientist.”

I was so, so down for the rest of that meeting. You could have scraped me off the floor.

But then this really funny thing happened. After the meeting, several faculty members approached me and they enthusiastically offered to help me install the plants. I was shocked. I mean, this isn't what serious scientists do. They don't think about lab waste. They don't like junior faculty making gardens and they sure as hell don't offer to help install one and one.

One, Jenny Davis even saw this greater meaning for the garden. It could help students who have been made to feel uncomfortable in science feel like they belong in a scientific environment. So that when a whole lab puts its hands to earth and thinks about how their actions affect the land that they're on, it makes science more inclusive.

I just couldn't believe it. Other people in my department thought this project was important and it had real life meaning.

So that summer, my entire lab and a quarter of the faculty from my department came together and planted the 70‑foot once‑renegade‑now‑administratively‑approved‑and‑departmentally-enjoyed garden. Colleagues stopped by to say hi. They turned on their car lights onto the garden so that we could finish the installation after the sun went down. And my colleague Virginia even threw in some cash.

When it came time to initiate the indoor composting, my lab members and my colleagues saved their food scraps in these little, itty bitty plastic boxes so that we could put them in the ground behind the plants.

And when the microfauna showed up, pictures of butterflies and beetles started flying into my phone from students and faculty.

As the weeks passed that summer, I would write in my office for 25 minutes and then I would step over to the garden and watch the monarch caterpillars rhythmically chewing on milkweed leaves. Maybe I'd pull out an invasive plant species or two or I just sit before heading back to my laptop and working on this big backlog of tasks that had accumulated over the last year.

Another 25 minutes, I'd be back in the garden for another five. I'd be watching tiny little spiders crawl in and out of anise hyssop blooms or ants fostering aphids. It was so cool. It was like watching the birth of an ecosystem. I spent hours that summer watching the creatures in that garden.

More often than not, lab members would just pop by to do the same. And once, I even found a graduated lab student who was just passing through town sitting there.

As the summer of 2019 wound down, I actually faced some pretty big career disappointments. I had a scooping, there were paper delays and rejections and I was still nursing exhaustion from this six weeks of invited‑talk travel that past spring where I was home for only ten days in total. And I wasn't going to have a publication that year.

All of this was weighing pretty heavily on me this one evening when I walked up my office and shuffled down the stairs and sat down on the loading dock that sort of splits this garden. I was waiting for my husband in our car to come and pick me up. It was really, really quiet and there was this blue light that was spreading across the parking lot. I was sitting there worrying about job loss.

But then I shifted my focus. I turned from looking for the car to the plants beside me and I saw this tiny monarch caterpillar. It was just sitting on the underside of a leaf and it was maybe a day out of the egg. And I suddenly felt really at peace. My lab and I had tried to take responsibility for our actions. We were trying to do science and steward the space that we work in at the same time. And my colleagues in my department wanted this too. So the future kind of just felt lighter. And this caterpillar that I was looking at, it was part of but it's not the ending of all this growth and support.

And so as my car pulled up, I popped the trunk, poured my bags and books into the back and it struck me, I'm really not a serious scientist. And I'm fine with that.