In this week’s episode, both of our storytellers share times where they got stuck with jobs they never signed up for.

Part 1: Ted Olds finds himself an unwilling participant in his son’s school assignment to look after an electronic baby doll.

Ted Olds is a mechanical engineer and patent lawyer. He has worked on protecting technologies as wide ranging as Pratt and Whitney's geared aircraft engine to the Rainbow Loom. He also tells stories around the country. He has appeared on Story Collider and its podcast before. Ted has won the Moth Story Slams 20 across eight cities.

Part 2: Cadré Francis is less than thrilled when finds out he’s been volunteered to do demonstrations at a STEM camp.

Cadré Francis is a Ph.D. student in Materials Science and Engineering (MSE) at Boise State University. He has earned degrees in the biological and chemical sciences and enjoys studying MSE due to its interdisciplinary nature. Outside of work, he enjoys learning about history and playing sports. He hopes to pursue a career in research and development where he can contribute to more sustainable science while driving innovation.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

So, my wife Judy and I are in bed. It's 3:30 AM on a Saturday. She's quiet but I know she's not asleep. There's no way anyone in this house is asleep with this damn baby crying.

And I'm thinking, “I have to stop this. I've got to end this once and for all.”

Ted Olds shares his story at QED Astoria in Queens, NY in November 2022. Photo by Zhen Qin.

The crying, it's muffled and it's sporadic. It'll cry for a minute then it's quiet for 30 seconds and it starts up again. But, honestly, constant and louder would be better. That I could turn into white noise. This is like a dripping faucet. I have to strain to hear it and when it does stop, I'm thinking I'm just on edge waiting for it to start again. There's no way to fall asleep and I've got to get up in the morning.

The crying is muffled because the baby's in the laundry room and the laundry room door is shut. Our bedroom door is shut. The baby's in the dryer and the dryer door is shut. The dryer's not running.

Our son brought it home from school Friday. It's an electronic doll. It comes with a bottle. There was no warning that he was bringing it home. If there had been, we could have talked to the teacher, found out what you're supposed to do with the damn thing. But, no. No warning.

It's an eighth-grade health class project trying to teach 13-year-olds, these hormonally‑challenged 13‑year-olds you don't want to have a kid anytime soon.

So, anyway, it was quiet for a while. And then we're just finishing up dinner, say, 7:00, and it starts crying. Judy and I, we look at him like, “You're on,” and he says, “What am I supposed to do?”

I said, “Well, there's a bottle. I mean, I would try and feed it.”

He says, “Yeah, yeah. I know that. But then you're supposed to do other stuff. There's some things you're supposed to touch it and handle it and it's got to be in a certain order.”

And I said, “The teacher must have told you.”

Ted Olds shares his story at QED Astoria in Queens, NY in November 2022. Photo by Zhen Qin.

He said, “Well, she was talking but my friends were all making jokes about me having a baby and so I didn't really listen.”

Now, this is 20 years ago. We didn't have the teacher's cell number. We didn't have her home number. We had a landline number to the classroom.

I called it. I know it's a long shot, but maybe she's in, grading papers 7:00 PM on a Friday. But, no. No luck at all.

Judy takes him in the living room and they start trying stuff. She's our tech guru. She can solve anything. I mean, most stuff she solves in a second. If there is something complicated, I've seen her be on the phone with tech support for hours and trying to fix the next, the newest electronic thing way longer. I would have quit long before that. And she always sorts it out, so she's going to fix this. She's going to sort this out.

And they're trying. You know, feed the baby, cradle it, hug it.

“Waah, waah, waah.”

All right. Well, feed the baby. Burp it. Rock it.

“Waah, waah, waah.”

I say to our son, “Hey, do you know any other kids that have brought it home already?”

“No.”

So, I start calling people, people we know whose kids are in the same class.

Ring, ring. “Hey, it's Ted. Hey, has Johnny brought home the crying baby yet?”

“The what?”

Ring, ring, ring. “Hey, this is Ted. Has little Jane brought home the crying baby yet?”

“The what?”

After maybe a half hour, our son says, “That's it. I quit.” He goes to his room, closes the door and puts on music.

I say, “Judy, do you want me to make him come out?”

She said, “She's better off on her own.”

Now, here's the thing. We've got two kids. We've got a daughter who's a couple years older. When she was in eighth grade, they didn't do the baby. But both kids, we can't force them to do anything they don't want to do.

As an example, in seventh grade they had to learn a musical instrument and our son brought home the cello. They're supposed to practice every day. And so for a few days we had screaming fights with them and then we just gave up. I mean, he didn't practice at all.

But here's the crazy thing. There were five kids that played cello in that class, he was second chair. Like a kid who never practiced was somehow better than three other kids. It's got to be hell to be a middle school music teacher.

But, the thing was he got good grades and he was able to skate by everything in school, except, finally, school had found something he couldn't skate by. This baby.

Well, Judy keeps trying new stuff and I go to the computer and whatever the internet was 20 years ago, looking, hoping to find instruction. But I strike out. I don't find anything about how to make the baby stop. But I will give you a word of warning. If you Google ‘crying baby doll’, mostly, you get porn.

But the one thing that I did learn was I found this study that said a crying baby, their effect on parents can be the parents can get anxious, hopeless, depressed, angry. It can cause the parents not to bond with the kid. It can hurt the parents’ perception of the kid. And, in extreme cases, it can cause the parent to think about harming the baby and then they feel guilt and shame. And that's parents.

I was very anxious. I was completely hopeless. I was very angry. I didn't want to bond with this damn thing. I didn't care about this thing. And I wasn't just thinking about harming it. I was making plans to end this.

After about an hour, Judy just said, “That's it. I quit.” I've never seen her quit before on technology but there you go.

So, we try to watch TV but, to drown out the baby, we had to make the volume so loud it was unbearable. And after a bit, she gets up, picks up the doll, walks down the hallway and I hear, “[loud] Waah, waah, waah.” “[soft] Waah, waah.”

She comes back and says, “It's in the dryer,” and we were able to watch TV. We could drown that out at a volume that wasn't too bad and we had a couple hours of peace.

The one thing I remember watching, there's a show called Malcolm in the Middle. And if you don't know it, it doesn't matter. It's about a family that has four sons and the youngest one, his name is Dewey, he just whines all the time.

In the episode that night, I remember he was just crying the entire half hour. It was like funny. It was like, in this dark humor way, it was funny to us, but we should have realized it was foreshadowing the rest of our night.

And at midnight, we go to bed. Now, it's 3:30 and, “Waah, waah, waah,” and I'm thinking, “I have to end this. This has got to stop. I can't deal with this anymore.”

Ted Olds shares his story at QED Astoria in Queens, NY in November 2022. Photo by Zhen Qin.

But I'm thinking, “Well, wait a minute. I don't want to ruin the lesson for my son. I don't want him to have kids while he's still a teenager. Maybe we should all get through this evening.”

“Waah, waah, waah.”

“No, hell no. No, I've got to end this.”

And while I'm going through all this, suddenly, Judy jumps out of bed. “That's it,” and she runs towards the laundry room swearing. I follow.

The kids hear the screaming. They come out after and the three of us watch as she opens the dryer door, takes out the doll, rips off its gown and starts trying to open the battery pack cover. But, of course, it's locked. That point, you just take the batteries, what kind of lesson would that be?

So, she gets a screwdriver and now she's trying to pry the cover off. She's prying it and, with a crack, it pops open. Now, she's trying to get the batteries out, but they're locked in. So she's prying that out. Then, with another crack, the batteries pop out and they're hanging from the baby's back by a wire.

“Waah, waah, waah.”

She gets the scissors, “Waah, waah, waah,” cuts it. “Waah…”

That baby had been crying almost nine hours straight. I wish I'd remembered what kind of batteries they were, because those are some good batteries.

The kids and I looked at her with this mix of fear and awe. I mean, that's some coldblooded will right there to do that. But, like I said, she's our technology fixer.

She calls the teacher, the teacher's classroom. “Yeah, hi. Our son isn't doing the baby project anymore and you can charge me for the doll. I only wish I could call you at home at 4:00 AM and tell you right now.”

Do you wonder whether our son got the lesson even though we ended it early? Hell, yes. Both kids got the lesson better than they possibly would have if they had gone through dealing with the doll. They watched their mom destroy a doll for crying. Do you think they're going to bring a baby into that house?

Matter of fact, they're both in their 30s and we're still not grandparents. I think the lesson was just a little too good, perhaps.

Thank you.

Part 2

I'm sitting in my office in the first semester of graduate school in chemistry in Louisiana and I was wondering why some of my other friends didn't want some of these empty faculty offices. It's such a great idea. You have your own space. You can do whatever you want to do. And I didn't know I was about to find out.

The only bad thing about an office is people know where to find you.

I hear a knock at the door, the door I keep locked with the window I keep locked. I open the door and I see this older lady and I immediately start thinking, “Oh, this is someone's parent. I can’t talk to you. It's really great.”

Cadré Francis shares his story at Stueckle Sky Center, Double R Ranch Club Room in Boise, ID at a show sponsored by Boise State in November 2022. Photo by Mark VanderSys.

But then she starts speaking about a STEM camp and there's this Chemistry Week and I should do some demos. And I remember reading an email a few weeks earlier and ignoring the email a few weeks earlier. She keeps talking and talking and I'm wondering why is this lady not listening to me say no.

Little did I know, she had just spoken to the department head and he said, “Oh, yeah. He just finished lab. He's probably down in his office. The semester is almost over. He's going t have a lot of free time. It's going to be great.”

So, it took about five minutes of me saying no and she saying, “Oh, no, it's already agreed. The department head said yes and we're really excited to have you,” and I realized it was no longer a question. She was just simply informing me that I'd be there and to give her a list of demos that I'm going to do and what materials I’d need.

I accept it. Not much of a choice at this point.

So I said, “Well, I got to put up a resistance. What I'm going to do is I'm going to do really boring demos. That will really show her and show those campers. It's going to be super boring. Everyone's going to fall asleep and I'm not going to care.”

So, I send an email with the list and then no answer. I'm excited. I'm like, “Oh, maybe she forgot.”

A few days later, I got an email back. “Oh, wouldn't it be great if you actually met some of the campers before so they know who you are? So they can know what you're doing and be more engaged when you're doing the demos.”

And I thought, “Yes, this is great. This is exactly what I want to do with my free time. It's not like I just spent the whole summer teaching two labs, taking a class and doing research. So, sure, I love to come and work for free doing these demos and be a camp counselor.”

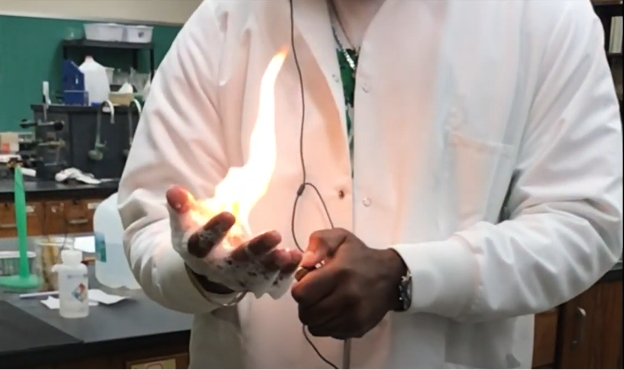

I go to the camp. The campers aren't that bad. They're actually pretty cool. They're interested in STEM. STEM is cool. So I thought, “Ah, well, I wish I had planned some cool demos. Maybe I should have done some butane bubbles and light myself on fire. Maybe I should have done a giant elephant toothpaste. Maybe I should have done a pulse jet engine. There are so many cool things I could have done but I didn't plan it. And if I asked them now for the materials, obviously, they're going to know that I didn't care initially, so I have to stick with it.”

Cadré Francis shares his story at Stueckle Sky Center, Double R Ranch Club Room in Boise, ID at a show sponsored by Boise State in November 2022. Photo by Mark VanderSys.

Day one and day two go well. The demos are super easy. As I was saying, I could do it in my sleep. And most of the campers, some five‑year‑olds could probably do it in their sleep too. There was nothing to write home about.

So, day three comes and I have a few demos planned. They're all going to be, again, super easy, super boring.

I do the first one. It goes well. Woohoo. The second one, I'm going to take a hard‑boiled egg. I'm going to remove the shell and I'm going to put a piece of paper, light it on fire, put it in an Erlenmeyer flask and the difference in pressure is going to suck that egg into the Erlenmeyer flask whole. Woohoo. Super interesting.

So, I light the paper. It starts to smoke. I'm like, “Ah, well, there's a smoke detector.”

I put it in the bowl of water and, because I'm so smart, obviously, I'm a graduate student in chemistry, I'm brilliant. I decide don't get a different piece of paper. You take that piece of paper out, you dry it as much as you can and then you pour a bunch of rubbing alcohol on it. That's the way to get a fire started.

So, I pour the alcohol on. I rub my hands. I'm like, “Yeah, this is going to be great. It's super easy.”

And I light the paper on fire, and my hands with gloves on fire, and I'm thinking to myself, “Well, you could’ve just done this the right way and not done it this way.”

So I'm on fire and I'm thinking, “Well, you were telling everyone you're this awesome scientist. You definitely can't put your hands in the bowl of water that's sitting right there because they'll know you made a mistake.”

Some of the younger campers are laughing, super excited. Some of the older campers are super excited as well. And some of them are looking at me like, “Ah, we're not sure that that's what's supposed to happen.”

Most of the adults seem like, “Well, yeah. That's all part of the plan.” They aren't concerned. They're just watching me.

You always hear that when something bad happens, everything slows down. I start thinking, “Well, if I start a fire, the fire department's going to come, then some parents are going to drive by and they're going to see all these campers outside with the fire truck and then someone's going to explain, ‘It was that chemist.’”

Then I say, “Oh, well. Maybe the sprinkler system will go off,” and I'm like, “No, that's not how it works. One person on fire doesn't set off a sprinkler system.”

So I'm looking at my hands and I'm like, “Well, you've really done it now. You've messed up. But you got to keep it going. The kids are so joyful. You don't want them to think that science is dangerous, that you are doing something you're not supposed to be doing by playing with fire.”

And I'm like, “Well, I can let it go a little bit longer.”

My research is in the swamps catching alligators, but this is how I get hurt. Imagine having to tell my friends, “Oh, how did you get hurt? Oh, was it in a swamp?”

“Oh, no. No, it wasn't.”

“Oh, you were doing some synthesis.”

“No. No, not really. I was doing a STEM demo and it kind of got out of hand.” It would be super embarrassing.

Everyone knows that I enjoy people who speak with their hands because they get really expressive when you bring up a passionate topic. They do some of this and it's super interesting, so I start doing some of this and I'm cooling it down. It's not working. The fire's still going.

I can feel my skin burning at this point and I'm like, “Oh, well. Maybe now is a good time to out it.”

I'm like, “Oh, well. The egg is in the Erlenmeyer flask. Ooh, the experiment's over.” I put my hands in the water and I out it.

My pride's not really that hurt. Most people thought it was a bug. I mean, sorry. Thought it was a feature, not a bug. So I kept it going and I really enjoyed the camp. I ended up planning some more activities for the next few weeks.

For the next summer, I became assistant director and helped plan the activities. The students were super excited. When they got picked up, they're like, “Oh, yeah. That's him. That's the counselor who lit himself on fire. It was super cool,” and it made me feel good. Some parents didn't really find it that funny but it was okay.

Then a little bit later, a few weeks later, they decided to put the camp, make it available for the following year. Chemistry Week was sold out immediately. “There's this guy who will light himself on fire. It will be fun.”

The following summer came and the campers evolved. They lied and they changed the story. They're like, “Oh, he's the Ghost Rider. His whole body was literally on fire. You should have been here last year.”

Cadré Francis shares his story at Stueckle Sky Center, Double R Ranch Club Room in Boise, ID at a show sponsored by Boise State in November 2022. Photo by Mark VanderSys.

And, you know, I could light myself on fire in a safe way but I didn't do it. So the campers are really cool. Unfortunately, I think the more you learn in science, the less imagination you have. They can take some things we find so simple and it'd be the most interesting thing in the world for them.

So, I really enjoyed that. I spent every day at the camp. I made excuses to work long hours to stay there all day. I said, “Oh, it's the summer in Louisiana. My power bill will be high, so I might as well just stay, work all day.”

Even the day I defended my Master's thesis, I showed up to work. I wasn't on the schedule. I wasn't getting paid. And I was going to be in a building 15 feet away from my Master's thesis. And I thought, “Oh, well. The campers could distract me. It'll be fun.” It didn't really work out but I ended up passing, so I'm here today.

And if you're going to do something, you might as well do the best job you can, because you may just end up lighting yourself on fire anyway.